Single Threaded Leadership

Summary: Single threaded leadership is better than functional leadership, but is harder to hire for and execute. It is the best way to create true scalability and results-oriented teams in a technical organization.

“Do you want to be a PM or an EM?” asked Jess on our phone call. It was 2013 and I was going through an M&A process with Twitter to sell my tiny startup.

I’ll admit at this point in my career the notion of an “Engineering Manager” and a “Product Manager” didn’t mean anything to me. I might have had to Google the definitions.

As the CEO of the company I had hired all the engineers, managed them, and owned the product roadmap.

After hearing her out I said something like “I guess I’d probably be a better product manager?”

To me, deciding what to build felt incrementally more on target for my skill-set than a role more focused on delivery of the build - though I wasn’t sure exactly how to separate the two.

A day or two later she called back “We don’t actually have a headcount for a Product Manager, think you’d be ok being an Engineering Manager?” I shrugged and agreed.

The Functional World

Over the next few years I found myself in, what I learned, was a traditional “EPD” or Engineering, Product, Design org - where the organization was built around functional reporting lines. There was a VP of Engineering, VP of Design, and VP of Product - all reporting into the CEO.

Some organizations put some twists on this - perhaps the Head of Design reports into the Head of Product - or maybe there’s a CPO who owns all Eng, Design and Product - but go a level or two down into the org and you quickly hit a separation of functions with a deep tree of functional reports: All the engineers over here, all the product people over there.

This was also my introduction to ladders and levels - a structured rubric for determining how senior and how well performing employees are within each function. At a place like Twitter circa 2013 these definitions carried with them the potential for enormous rewards in both cash and stock - so naturally they formed strong incentives.

Incentives

In machine learning one of the classic problems is models that get “overfit” to their training data. A simple example of this might be training a simple neural net to differentiate cats vs dogs - but neglecting to realize that all your pictures of cats are indoors and dogs outdoors – the optimization algorithm decides that any picture outside is of a dog and indoor pictures are, of course, cats.

Similarly, functional organizations give way to promotion and performance review processes that disproportionately reward the most engineeringy engineers, the most producty product people, and the most designery designers.

The things that become optimized for are projects that will appeal to the (often single function) leaders sitting around the performance calibration table. Engineers strive to have “scope” and “impact” and in many organizations this leads to an overgrowth of infrastructure and a pull away from customer facing results.

I remember hanging out at Dolores Park in San Francisco a number of years after leaving Twitter. I was kvetching to a friend, a very respected engineer who had a celebrated career at the company - that we, as a company, wasted so much money and time building infrastructure that was not needed.

The engineer gave me a little grin and said “Yeah - but I got promoted several times working on those projects!”

Accountability

I had a variety of relationships over several years as an EM - some of my PM counterparts became close friends with whom I collaborated closely. There were also some slightly more tricky counterpart relationships at times.

Good relationship or bad, there was always some tension that the yardstick by which you're measured as an EM is different from that of a PM.

When I was an EM I was focused on ensuring I could hit delivery, hire and promote great engineers, and prevent incidents – while my PM was focused on a strategy that presented well. They were following the incentive structure: ensuring product leaders who would later sit in promotion and calibration committees would remember their slide deck and product pitch.

I saw this create incentive misalignments running all the way up and down the org chart. PMs could be rewarded for work that was unshippable - or punished when they had a great and executable strategy but happened to be paired with a lousy engineering team.

This created a dysfunction where functional staff would seek safety and control by exerting effort into things that were clearly in their domain - and avoiding solving for the messy interstitial spaces where a lot of problems emerge and value is created.

Later in my career at Twitter I was put into a more cross functional ownership role - not fully sanctioned as a GM but essentially a single threaded leader. This started leading to interesting conversations.

I had an engineer on my team who, let’s call him $cashtag, wanted to discuss his compensation package and prospects for promotion (every week). At one point we were discussing his favourite topic and I pointed out I couldn’t promote him yet because we hadn’t actually shipped the project - we'd only written the code thus far and were still working towards launch. I couldn't say we'd delivered business results yet.

Exasperated he declared “It just matters if I build it - if it doesn’t have business impact that’s the PM’s problem, not my problem, I’m an engineer I just build what they tell me to build.”

There you have it. The perfect articulation of why functional leadership creates the wrong incentives.

Many organizations try to band-aid these problems with concepts like a DRI (directly responsible individual) – but ultimately without some degree of control over team performance, bonus, hiring, and firing these labels are toothless.

It's probably not a coincidence that Stripe's engineering org around 2017-2019 was one of the most focused on business impact vis-a-vis performance and promotion I had seen - since during that era there was a pretty high degree of integration between Engineering and Product at the org level.

Single Threaded

The idea of a single threaded leader, and of small teams (2 pizza teams - i.e. a team small enough to be fed by two pizzas) was popularized by the excellent book Working Backward written by two former Amazon executives. Often technical teams are run either in a “Single threaded” model or a “Two in a box” model (where there is an EM and PM leader).

In 2016 I was sitting in a conference room at Stripe for an interview - I was working at Twitter at the time as a PM - having transitioned to an IC product role from my hybrid PM/EM role following the birth of my first daughter.

Patrick Collison, the CEO, walked in and the first thing he said was “Hi Noah, great to see you again. Why would you want to be a PM? You could just be an EM!”

At the time Stripe only had 4 PMs with maybe a couple hundred engineers. There was an expectation for engineers and EMs to own their own product work.

After I explained my desire to drive a product roadmap and strategy Patrick was quick to point out that he would expect this sort of product ownership from any EM - and assured me that I would have autonomy over my product’s strategies if I joined as an EM.

The next twelve months were extraordinarily formative for me. When I first joined I had a new grad engineer on my team who was fully driving a product roadmap all by herself. She was using AWS Redshift to find good prospective customers for the Stripe Invoicing product she was building, emailing those customers to get them to opt into the new product and give her feedback on her beta, and writing all the code.

I was super impressed. Of course - over time we found that yes, indeed, PMs deliver important value - but the more integrated the EM, PM, and Design functions are, the more team members are focused on customers, metrics, and delivery.

In the 2016-2020 era of Stripe we had a lot of discussions about how to create alignment and accountability with a focus on shipping for the customer.

A memorable debate included a quip about “Having one throat to choke” in a single threaded leader - where a proponent of the “two in a box” model pointed out that “God gave us two hands.”

Stripe implemented an explicit structure around single threaded leaders during this era - with good but somewhat uneven results. As is often the case, the devil is in the details.

Trade Offs

Claire Hughes Johnson (author of the excellent Scaling People), during an org design jam discussion on a whiteboard at Stripe in 2018 pointed out to me that no org structure is purely better than another. It’s always a question of what you’re trying to optimize for - and where you’re willing to take some pain.

Functional organization structures are optimized for hiring a lot of people quickly and ensuring they have good technical skills. They also optimize for a structured performance process oriented towards assessing domain specific skills.

Unfortunately what you often give up is speed in decision making, accountability, and overall business orientation.

Over the subsequent years I became convinced that functional organizations bred unaccountable teams.

In every technical organisation of some scale there is necessarily both a functional identity and a “mission” or product team identity. The main question here is which should take primacy.

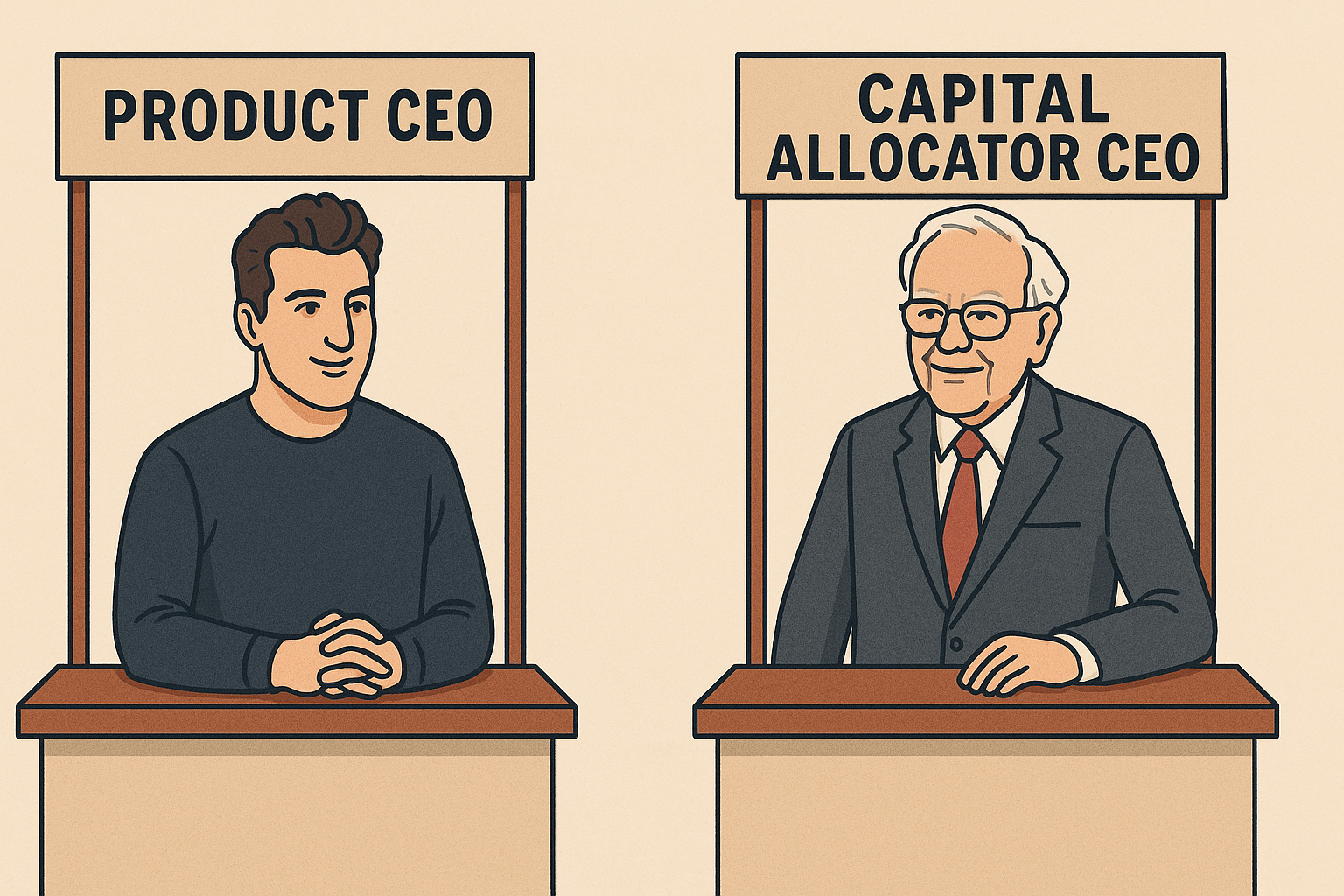

In an organization where the CEO is the ultimate product visionary the functional organisation may be justifiable (I think, iconically, this would be Brian Chesky at Airbnb). Airbnb isn’t really building multiple products - they’re building one seamless experience with many features and facets - and there is one man ensuring it is fully integrated.

To over simplify things one might articulate the “CEO as Capital Allocator” paradigm as an alternative to “CEO as Product Visionary.” In the excellent book The Outsiders author Will Thorndike profiles CEOs, including Warren Buffet, who tend to focus on M&A and empowering semi-autonomous units within their organisations.

In an organisation where you truly have many different lines of business and where you can hire amazing people to run businesses and teams I think one wants to be more like Warren Buffett and less like Brian Chesky.

Bezos at Amazon was certainly an opinionated leader - but the variety of businesses that Amazon built was so vast that I think it required a less centralized model.

Single threaded leadership can have critical failures - most notably where it can be hard to find the right people who truly span the functional spectrum and are able and willing to drill into the details either technical or product in nature.

Enter AI

AI can solve a lot of problems around technical knowledge deficiency or a need to share more context. It also reduces the number of people you need to hire to accomplish a mission.

The functional alignment is suited to an old school world where you need vast teams of people to manually grind out work. The functional org helps you rapidly hire those people, manage them, and allocate them interchangeably.

In a world where AI means you can get by with far fewer people - and where knowledge gaps can be cleaned up with a superintelligent computer sidekick I suspect many of the upsides of the functional org are lessened.

The inverse is not true - AI doesn't help solve alignment issues that functional orgs create. As AI tools help strong generalists fill specialization gaps, I suspect single threaded leadership roles to become increasingly common, productive, and high impact.

So this will tilt the tables further in favour of the mission oriented org structure.

Making it work

Being a single threaded leader is difficult. Finding good single threaded leaders is challenging.

The most important characteristic of a single threaded leader is a driving sense of ownership and responsibility - and an iron will to create the change needed in your team, product, and technology to deliver results for your customers. People who are successful in this domain almost invariably have strong personalities, strong opinions, and develop loyal followings.

The number one challenge for a single threaded leader is one of mindset. The leader must be almost infinitely curious - willing and interested to dig into anything that is blocking their team and gumming up the product. They must avoid the self limiting beliefs that create artificial barriers to their impact.

Some leaders will come from engineering backgrounds - and they must fully embrace understanding the business problems, the financial implications of their decisions, and the principles of good user research. Failure modes for engineering based single threaded leaders tend to be wasteful builds that customers don’t want.

Other leaders will lack the technical engineering background - and they risk shying away from asking the questions about and developing the internal mental model of the technical solution space. The self limiting belief here is the notion that they can’t understand some level of implementation detail - but the truth is that with enough raw intelligence, curiosity, and a supportive technical team (and perhaps some good AI tools!) they can probably gain a good-enough understanding of any underlying system to help drive the team’s decision making.

Trouble comes when the single threaded leader either doesn’t have drive or doesn’t ask the “obvious” question - doesn’t push the team to “ELI5” things they suspect might be important but don’t understand.

For the right leaders, though, the single threaded model is uniquely empowering - and fun - and this can lead to astounding business results.