Levels & Derivatives

A few years ago I began to more mindfully slow the increase in my lifestyle. This was a decision made to increase my, and my children's, long run enjoyment of life.

As humans we often think we care about the level of something (e.g how much money do I have?), but more often than not we care about the derivative (How much is my wealth increasing).

One of the most fundamental concepts I learned is the mathematical notion of the derivative. This can be colloquially simplified to be “change” - the derivative is the change in some value.

When there is no change the derivative is 0, when the change is at a constant rate the derivative is a flat positive value, and when the rate of change is accelerating the derivative is increasing.

The level vs the derivative

A non-monetary example: This is why so many people have trouble with Alcohol. They think they like being drunk. They do not. Being drunk is an unpleasant state of impairment.

What people like is the sensation of becoming intoxicated. The derivative.

The devilish thing about this desire is that it is inherently ephemeral. Once you’ve gone from 1 to 2 the only way to get the same sensation is to go from 2 to 4. This is why people end up too drunk. It’s why they’re often happy at the beginning of a night and less jubilant at the end.

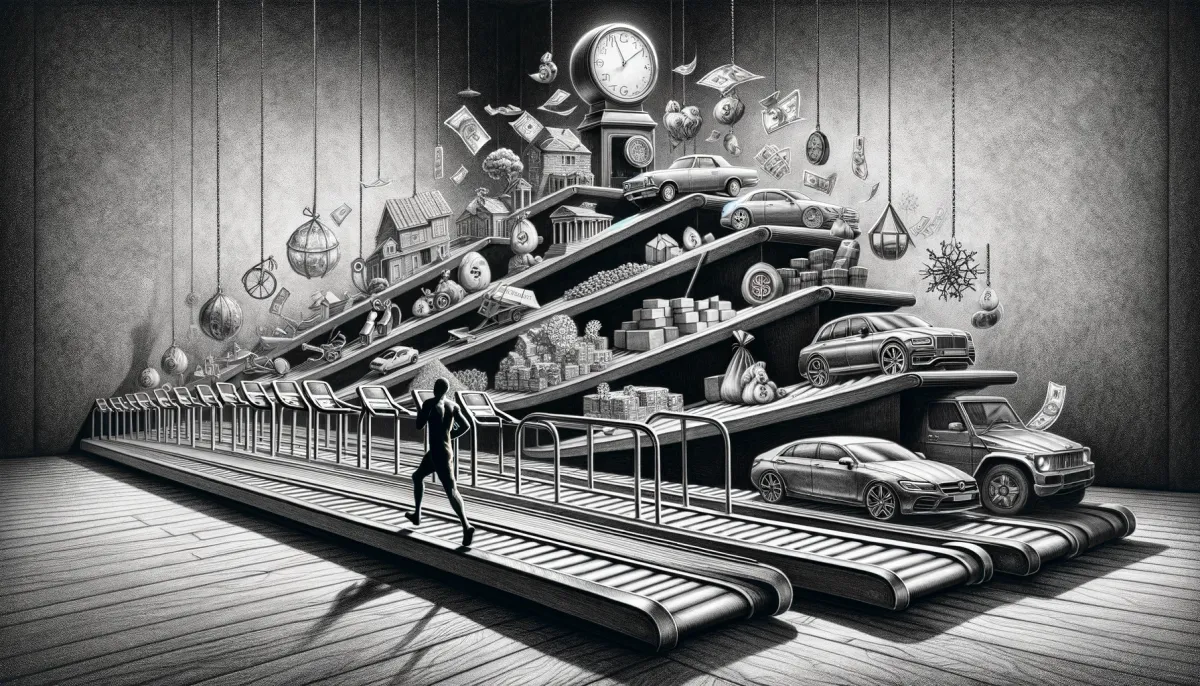

Hedonic Treadmill

This doesn’t just apply to alcohol, though, it applies to almost everything. The first time you fly business class it’s incredible. The first time you eat a Michelin star meal it blows your mind. The first time you drive a really nice car you’re ecstatic.

You think you enjoy the experience - but some of that utility you're getting is actually enjoying the gap between this new experience and prior experiences.

Subsequent experiences of the same sort tend to have a sort of decay to the enjoyment - they're good but not quite as good as the last time.

People habituate to things quickly - and this is widely referred to as the Hedonic Treadmill. My point here is not novel - but it’s worth reiterating because it’s so hard to remember and so important to absorb.

We sense the derivative more than the level.

If we generally upgrade our lifestyle from one level to another we're going to expertise a blip of happiness while we get used to things being better - but then most of us will end up taking that new standard of living for granted.

Upgrading your lifestyle risks feeling like just a blip of happiness

It’s hard to keep improving lifestyle, though. Even if you’re really good at making money - you’re going to run into problems of a psychological variety.

The problem is the often documented and discussed decreasing marginal returns to more money.

Mo money; incrementally less comfort

Why is this?

First: It's when you have the most unmet needs that additional resources gives you the greatest gains. If you've never had a hot shower, or your own bathroom within which to take hot showers these things will be huge lifestyle upgrades.

If you start from a low base the early gains you can make in lifestyle feel amazing.

In the fantastic book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, the author points out that from 1870 - 1970 we had this incredible set of lifestyle improvements that are unlikely to happen again.

The difference between having to spend all day hauling water and fuel into our homes and human waste out of it – and having piped water in and out of homes along with electricity is hard to compete with in terms of a quality of life change.

Second: The higher the standard of living you have - the harder it is to have a significant improvement over that standard of living.

Benchmarking

Morgan Housel writes about a friend who grew up poor and now still has this incredible level of gratitude and happiness when he eats a hot meal.

So, we seem to judge our lives by the derivative - with some memory in there about what things used to be like.

I was fortunate to grow up in a middle class home in a prosperous part of a prosperous country. I was comfortable as a kid - but surrounded by people who were more than comfortable (and this, I'll admit, often made me envious).

In retrospect now I feel fortunate to have started off with a comfortable but not luxurious standard of living which has allowed me to relatively attainably shift my standard of living up over the last several decades.

I never flew business class until my late 20s. My first Michelin Star meal was after going through the Twitter IPO as an employee.

I had plenty of nice things when I was young - but importantly there were (and still are) a lot of nice things yet to try.

I have some hedonic runway ahead of me. My lifestyle maybe started out at a 6/10, and has crawled up to an 8.5/10.

If I was doing it over again I think I'd have increased my lifestyle even more slowly but it's hard to go backwards. It hurts more to decrease lifestyle than it feels good to increase it.

Loss Aversion

“Loss aversion” is the concept in economics pioneered by Kahneman and Tversky in the 1990s which essentially put some formality around the notion that losses hurt more than gains feel good.

When acclimatised to luxurious living, normal life feels bad. For those who have benchmarked themselves to ultra-luxury even normal luxury will feel bad.

Now, when I have a just okay meal, fly economy, stay in a middling hotel - these things that previously would have been pretty good, sometimes feel a little bad.

In this sense, greater success leading to ever more refined taste and more luxurious consumption means an ever narrower window of experiences that will make you happy.

That doesn't sound so appealing to me. Who wants to have ever less things that will make them happy?

This problem compounds even further with children.

Levels, Derivatives, and Children

We want the best for our children, what does that mean we should give them?

What does spoiling a child mean? One useful definition I might put forth for spoiling a child is: Habituating such a high lifestyle that normal life feels intolerable to them.

The cliche is that spoiling a child will make them unpleasant to other people - but I think there’s something deeper going on here. If you spoil your children you will give them fear - because there will be so much to lose. You’ll also rob them of the ability to experience the pleasure of increasing standards of living - or at the very least you’ll severely curtail it. You destroy their derivative.

A child’s happiness over their life will be strongly correlated with their lifestyle derivative. If you benchmark their lifestyle too high at the beginning you may turn short term enjoyment into long term discontentment.

I believe this is why so many mental health issues are diseases of wealthy civilizations. This is also why so many people who come from desperate situations find themselves happier than those raised in relative plenty.

As Charlie Munger has quipped, and Morgan Housel has expanded on - one secret to a happy life is low expectations.

Anyone who is raised with too much will not just have high expectations, but due to loss aversion will stand to lose more than they stand to gain before they’re even in grade school.

What do do about all of this? Constrain your lifestyle & purposefully reset your expectations

Constraining Lifestyle

So, even if you’re so wildly successful in the economic domain that you could entirely remove all budgetary constraints for your family, the most rational thing to do to ensure long term happiness and mental health is to find the minimum lifestyle you, as an adult, can tolerate and live that way.

This will set your children on a course to gently and gradually increase their lifestyle over time. This will, I believe, lead to greater happiness.

Reset Experiences

I’ve found I can reverse this somewhat through various forms of fasting or seeking “reset experiences” that help me appreciate what I have.

Staying in less nice hotels makes me appreciate nicer hotels. In fact I almost always schedule our vacations such that we stay in the least posh hotel at the start of the trip - and the nicest hotel at the end of the trip.

I really dislike being away from my family, but when I travel for work I more acutely appreciate how much I love and miss them.

I often fast for ~18 hr - when I eat after an 18 hr or 24 hr that next meal, even if not particularly spectacular, is really really good.

Multiple times I’ve gone from comfortable well paying corporate jobs to doing a startup - something that is destructive in both ego and lifestyle.

These resets produce managed "low” experiences that pave a path for better "high" experiences.

Stoic philosophers and practitioners have techniques to avoid taking all that you have for granted including negative visualization. Seneca, one of the richest people in Rome in his day, would do a "practice of poverty" where he temporarily lived a simpler life - such that he could more greatly enjoy the vast wealth he had.

More on this in books like A Guide to the Good Life and Meditations.

Conclusion

Paradoxically the path to the greatest comfort over your life is not to hit the highest level of consumption you can afford - but instead to start with the lowest comfortable level of consumption you can tolerate and then gradually raise this level over time.

Budget constrained parents worry about providing enough. I think parents with less resources should take more comfort in leaving more hedonic headroom for their kids.

Budget un-constrained parents worry about providing too much. They should. It is easy to benchmark kids to unrealistic standards of living that will alienate them from much of society, and set their standard of living such that there is little hedonic headroom.

The more you limit yourself now the more you save not only financial resources - but also hedonic headroom - for generate future enjoyment.

This is how you build a positive lifestyle derivative.