Financial Relativity

When you are courting a nice girl an hour seems like a second. When you sit on a red-hot cinder a second seems like an hour. That's relativity. - Albert Einstein

There is a simple way to structure your investment portfolio to match unanticipated future needs. Every investor's goal is to have enough money for all their desired outlays - whenever those occur and however much they are.

This is an almost unhelpfully general statement - but within it there is an important and essential truth. One goal is contingent upon another goal. How much you need is about how much you want to spend, and when you want to spend it.

This line of thinking is sound but quickly runs you into a new set of problems: You may not be entirely sure when you will need how much. It's all well and good to know how much your rent payment is next month – but how will you know what it is likely to be in 20 years?

The trouble is financial relativity - that financial needs and outcomes are the result of a tangled web of interrelations that make it hard to predict what will happen.

To avoid running into serious trouble we must adopt a appropriate level of epistemic humility: Being unsure what will happen.

This does not mean we need to become helpless, though.

Fortunately for us financial relativity also delivers us some latent structure in the economy that can help position a portfolio such that is likely to deliver us the results we need without us needing to know what the results may be.

This sounds like sorcery, but it is not. Let me explain.

Standard Financial Advice

Good, oft repeated financial advice: You must invest your money to have enough for retirement. Your investment policy should depend on when you need the money. If you don't need the money for a long time buy a diversified basket of equities. If you need the money sooner then short duration bonds or cash may be more suitable (as I discuss in Allocating Capital: Fixed Income).

Why is this good advice? Equities provide higher returns in the long run, but can have volatility (sudden price changes) in the short run. Safer investments have lower returns but less volatility.

These answers aren't wrong but they are incomplete and don't fully explain why.

There's a difference between knowing a best practice and knowing why it works.

If you don't know how the game works it makes it harder to stick to a plan during ups and downs and it makes it easier to get caught up in fads.

Relativity

In Helgoland, a book about quantum physics by Carlo Rovelli, the author puts forth a memorable description of relativity involving someone walking across the deck of a boat as the boat navigates the sea. How fast the person is moving is completely contingent upon the frame of reference. Is the frame the boat? the sea? the planet? Space as the planet hurtles through the solar system?

The simple notion of speed is in fact completely contingent upon context and frame of reference... it is relative.

How fast the dot moves depends on your frame of reference - the line or the scene?

Wealth and income, by themselves, are irrelevant measures.

Don't believe me?

If I told you that I have £500k in a diversified real estate, stock, and bond portfolio - would you think I am rich?

First - Without any other context, your answer will depend on how much money you have, where you live, how you grew up, and who you know. You'll immediately think about your bank account, your spending, and what you've read about financial matters.

There are a lot of people who would say yes. Many others would would say no.

Second - If I tell you that I can happily live in £20 per day, or £5300 per year, which is about 1% of my net worth you may perform some calculations or modifications to your assumptions that shift your answer.

Now am I rich?

Third - If I tell you that I'm living in the year 1776 your perspective will probably shift drastically. Adjusted for inflation that £500k GBP would be worth £68m.

How about now?

Financial assets are only meaningful in the context of things we want to afford and how we compare ourselves to others.

Inflation: Prices over time

Inflation makes prices across time hard to compare because the value of money is illusory and ephemeral. Economists and financiers today talk about "real" vs "nominal" prices where nominal prices are the dollar amount, but the real price takes inflation into account according to some benchmark.

The real vs nominal value of $100

The nominal value of $100 is always $100 - but the real value changes depending on what year you index from.

It can feel like the cash in your pocket is more real than the ownership of stock - but this is an illusion, and potentially costly one.

Real vs Nominal

The notion of real and nominal values was introduced in the 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith:

In this popular sense, therefore, labour, like commodities, may be said to have a real and a nominal price. Its real price may be said to consist in the quantity of the necessaries and conveniencies of life which are given for it; its nominal price, in the quantity of money.

In this almost 250 year old book he points out that nominal values don't really matter - real values do. Real values are what we can actually consume and use:

The labourer is rich or poor, is well or ill rewarded, in proportion to the real, not to the nominal price of his labour. The distinction between the real and the nominal price of commodities and labour is not a matter of mere speculation, but may sometimes be of considerable use in practice.

What Smith means by this is that the actual goods you want and need are "real" while the measure of money is just a placeholder numerical value or "nominal" value.

The obvious point here is that you use money to transact - not because it's actually valuable.

It is not because wealth consists more essentially in money than in goods, that the merchant finds it generally more easy to buy goods with money, than to buy money with goods; but because money is the known and established instrument of commerce, for which every thing is readily given in exchange, but which is not always with equal readiness to be got in exchange for every thing.

I want enough money to go on vacation a few times a year, own a nice home, eat sushi, have a membership at the best gym in my city, and buy my kids all the ice cream they want.

It's not the money I want, it's the home, gym, ice cream, and sushi... and all the things I want to consume in the future I haven't thought of yet.

Inflation Diversity

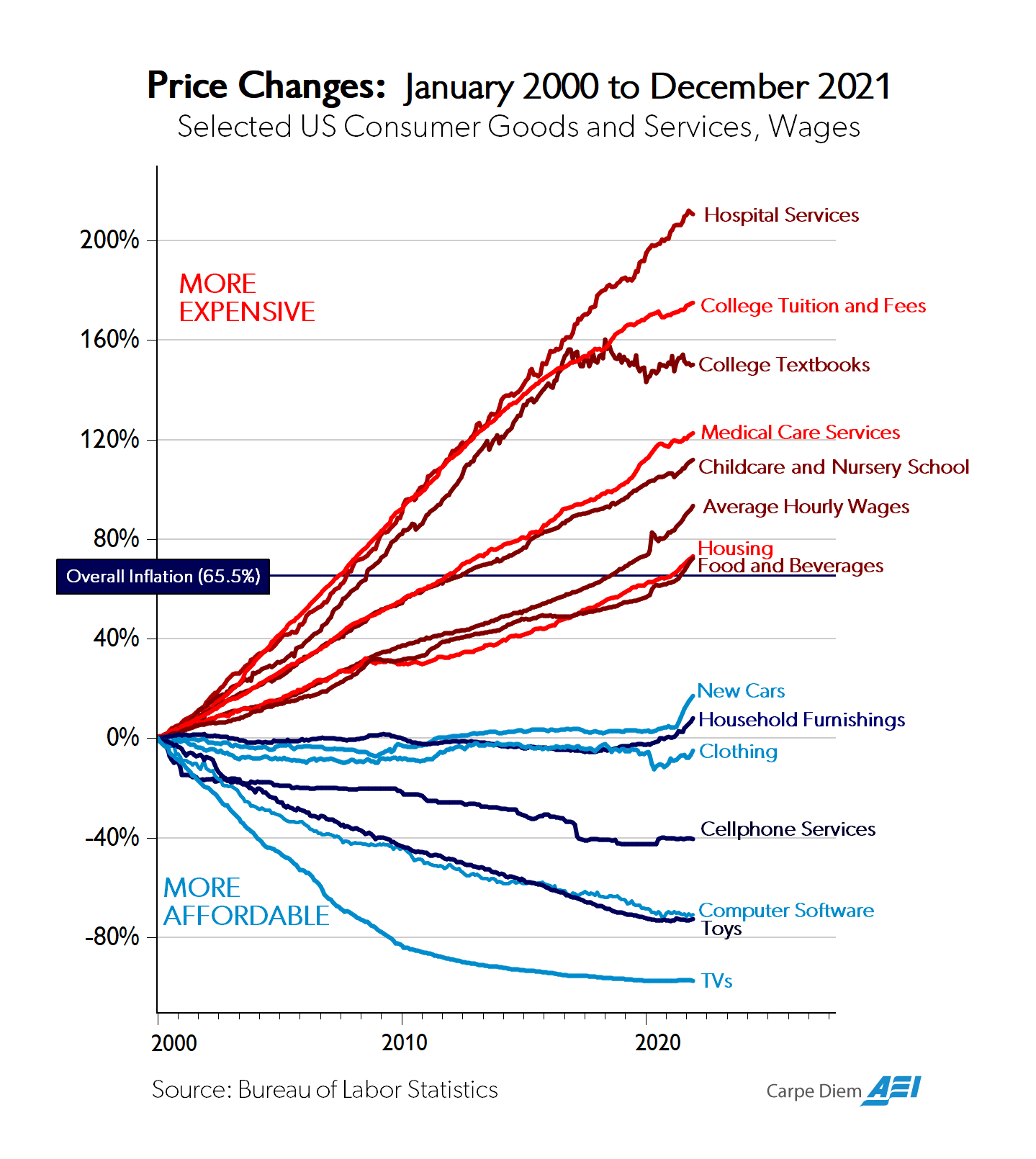

You may have seen the so called "Chart of the Century" that depicts the change in prices since the year 2000 across various goods in the US.

While overall price levels rose 65% between 2000 and 2021 the change was not uniform. Some things declined in value (in some cases massively) while others increased (in some cases massively).

The reasons for this dispersion are multifold and relate to regulatory environment, market dynamics, technological advancement, and consumer preferences.

The thing is you can't know where or when the inflation will show up. You have to adapt that attitude of epistemic humility - not being sure what will happen - and be prepared to live in any number of possible worlds.

Fortunately - behind all of these price changes and economic fluctuations there exists the real economy - companies that are producing goods people want to buy and relentlessly seeking new ways to please their customers, reduce their costs, and increase their prices.

This constant pressure of competition between firms for customer business produces all of the change that later shows up in our inflation and GDP metrics.

Real assets

Real assets are the means to produce things we actually want to consume. A house you can live in, shares in Apple Inc, ownership of a diversified ETF like VTI.

These assets aren't merely a stored medium exchange like gold, cash, or Bitcoin - they are entire or partial ownership of a productive asset that can provide direct benefit and/or future earning potential.

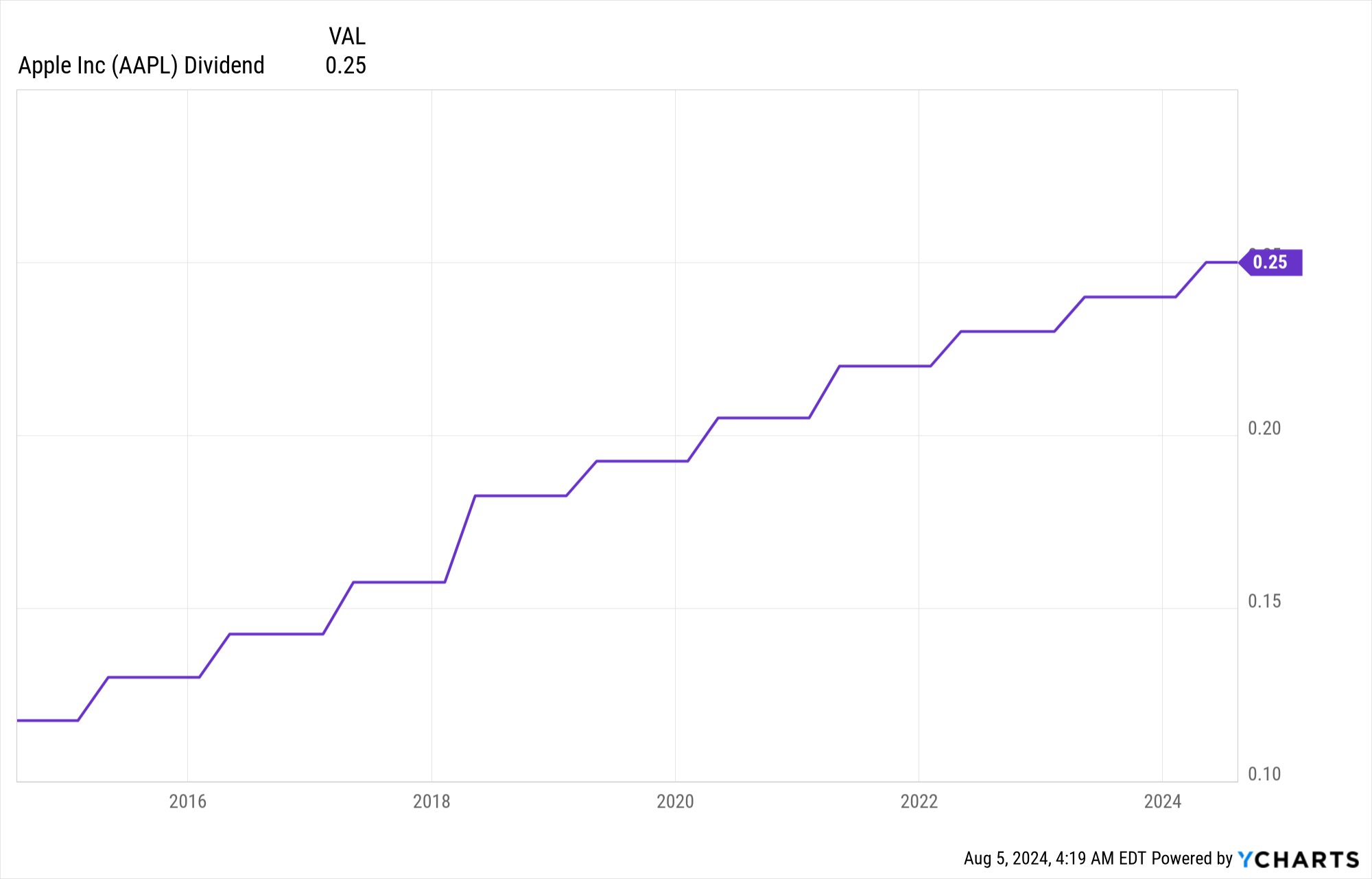

When you buy a share of Apple you're obtaining a fractional claim on all the future earnings of the company. Each iPhone they sell translates to some tiny measure of money accruing to you. As a dividend payer Apple pays out some of its profits to you as a shareholder.

The dividend is going up because Apple's business is growing, they're making more profit, and they're returning more money to shareholders.

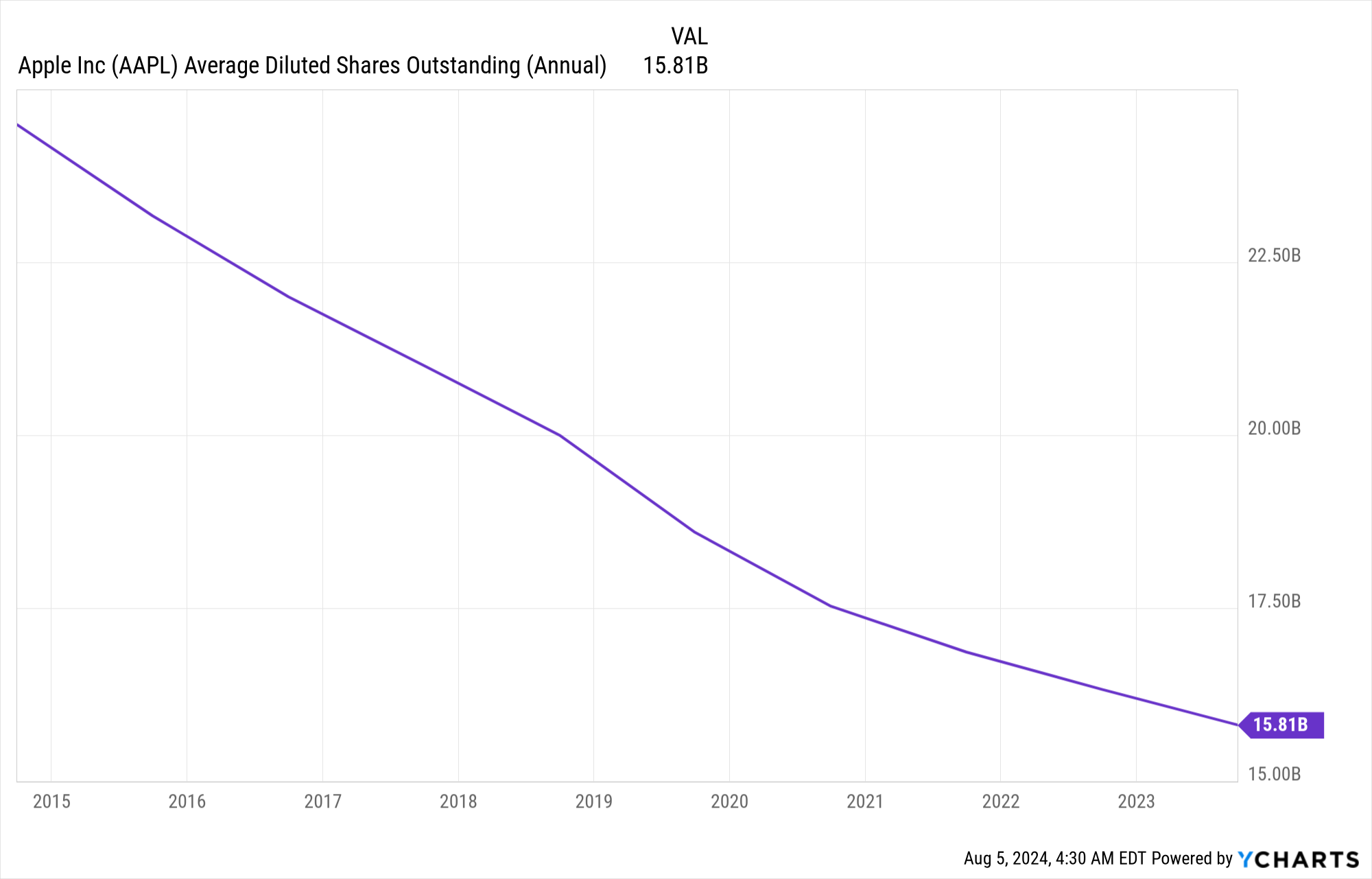

Not only are they returning money through paying more dividends - they're also buying back stock. In a stock buyback the company purchases shares and destroys them. The result of this is that the same pool of revenue, earnings, and dividends are shared amongst the fewer remaining owners.

So while the Apple share price might whip up and down quickly the revenue, buybacks, and dividends trudge along more steadily.

One of my favourite examples of this behavior is looking at carefully managed real estate firms during the 2008 financial crisis. This crisis hit real estate especially hard, caused a lot of investors to be wiped out, and drove asset prices down dramatically.

Let's look at Income Reality (Ticker: O) a REIT that owns the land and buildings that stores like Walgreens, 7-Eleven, and Tesco lease to run their operations.

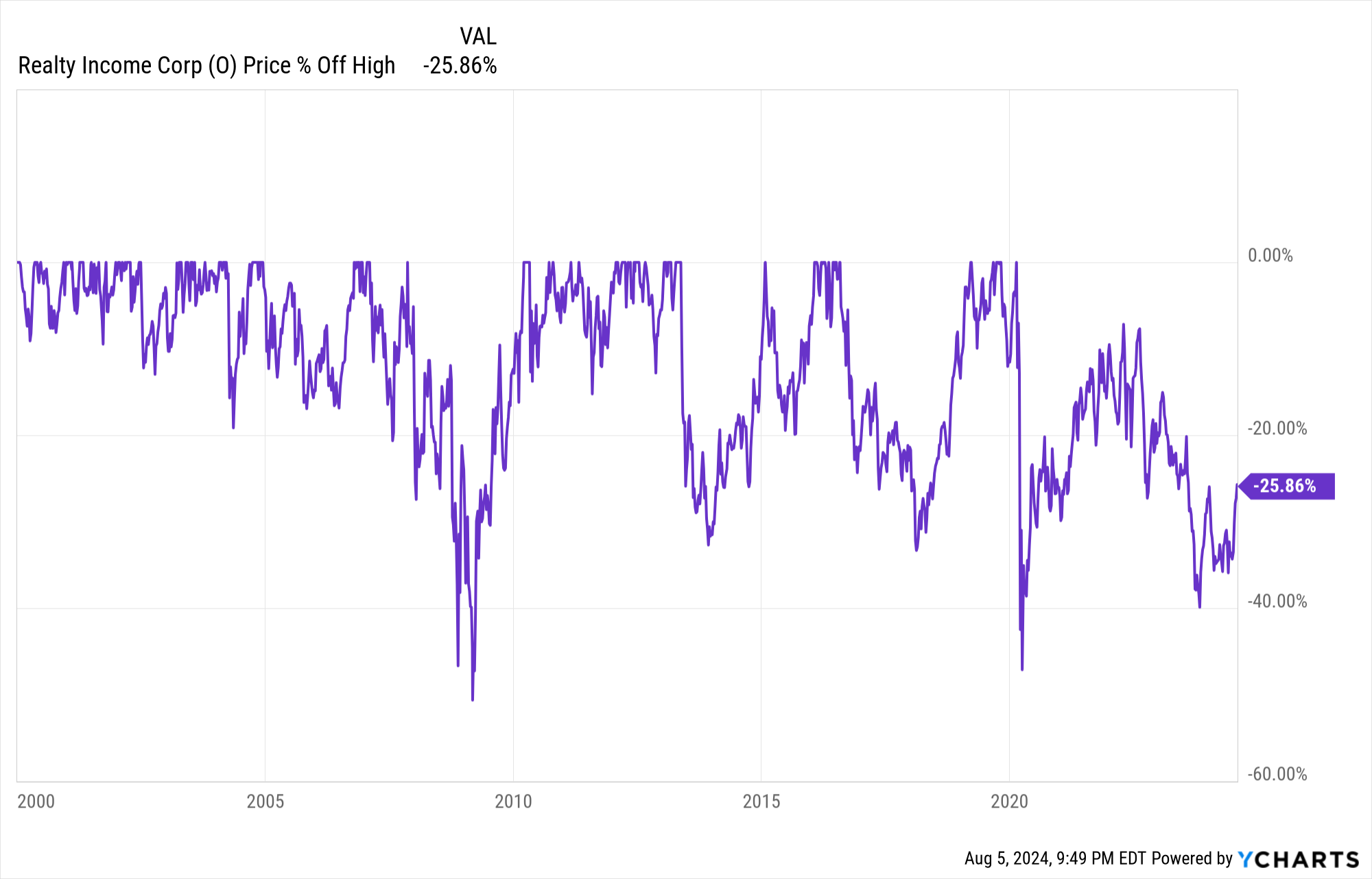

Since the year 2000 the stock has gone up - but had some pretty stunning drawdowns as well:

It can be hard to appreciate the drawdowns - especially those in the past - so if we look at this as a "percentage off the highs" chart we'll see how much of the value was lost - quickly - due to market volatility:

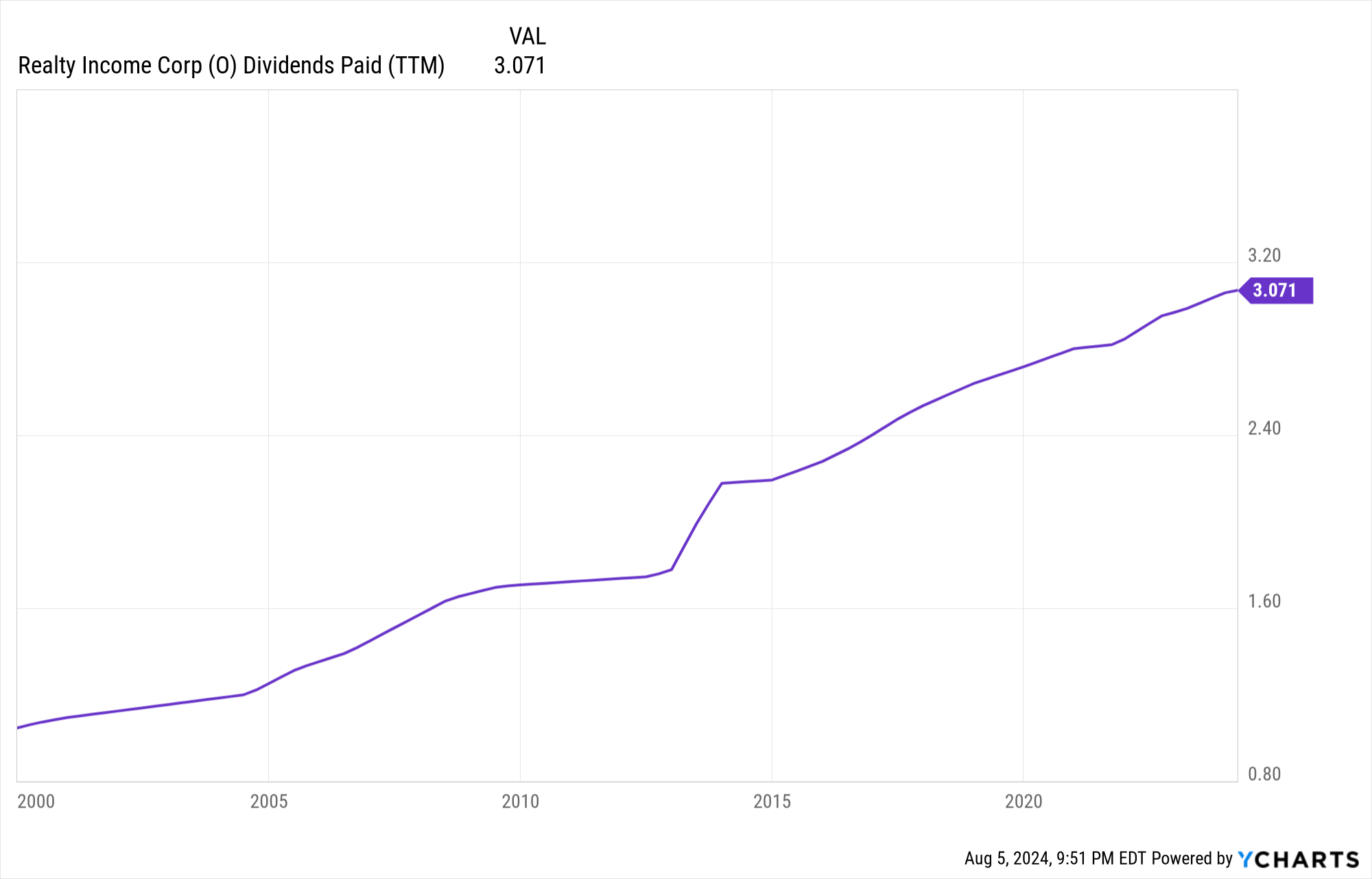

The thing about Reality Income is that, as its name suggests, it not just about the value of the stock - but the actual income stream it is producing.

We can look at a chart of the trailing twelve months (TTM) dividends - this is the amount of income an investor would have owned for each share by holding for a year.

The amount of income is at an all time high - despite the stock being in a 25% drawdown. Most interesting to me is that even during the 2008 financial crisis the company maintained a consistent payout.

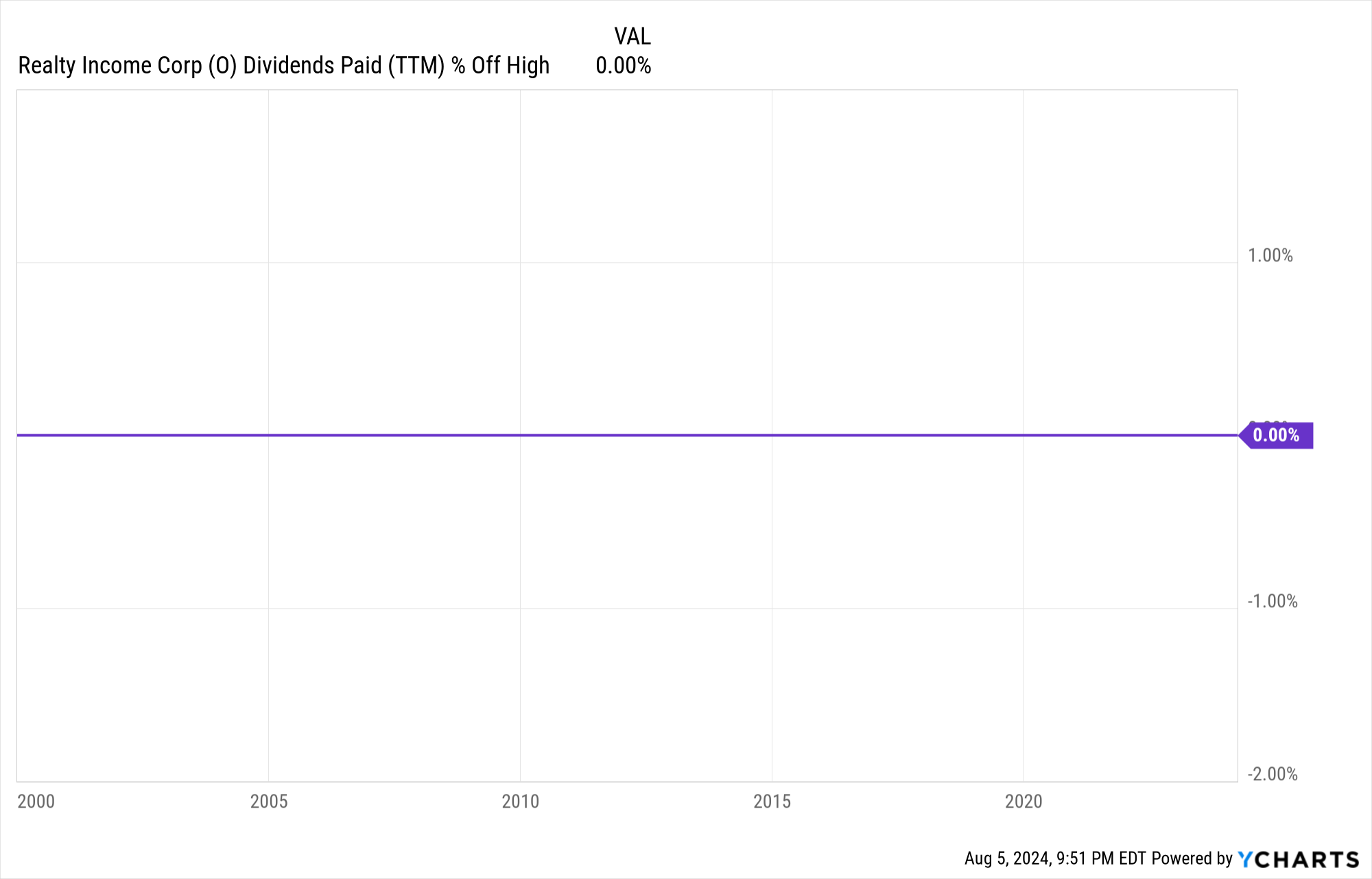

In fact if you try to chart a "% off the high" view for the TTM dividends you'll see that they've never decreased the payment over the last 24 years:

This, in essence, is one of the key differences between thinking about owning "stocks" vs "a business" - there can be massive volatility in what investors are willing to pay for a given stock but if you focus on a great compounding business you can ignore the day to day fluctuations.

I bring up these points about dividends and buybacks because they're central to the belief system of the stock market. The point is not that you should only buy dividend paying stocks, or (dangerously!) chase high dividend yields.

Rather, the point is that stocks are valuable on a fundamental basis because investor believe that in the future there will be some sort of return of capital to them - either by someone buying the stock or the company paying a dividend.

A good example: Google is finally now paying a dividend after decades of success building a massive business and accumulating a huge cash stockpile.

Market Indicies

So far we've talked about individual stocks. Theoretically you could say "Ah! I will want to buy iPhones, use the Web, drive a new Ford every few years, rent an apartment in a major US city, and buy my groceries at Costco" and buy a portfolio of $AAPL, $GOOG, $F, $AVB, $COST.

This would essentially make you an owner of the companies you rely on for goods and services you consume. In the scenario where the economy heats up and prices increase that basket of companies will gain more revenue - and if well managed - more profit. If the economy doesn't do well we'll likely have less inflation and you're short term reserves will support you.

By owning the slice of the economy you consume you need to think less about all the ways that economy might change. You're pairing investment real assets with future real spending.

A fun side note: There's even a startup, Grifin, that offers an investing product to help you allocate investment to the firms you shop at the most.

Coming back to our dot on a line - owning real assets puts you on the moving line - you're going to flow with the whole economy helping you maintain purchasing power.

How fast the dot moves depends on your frame of reference - the line or the scene?

Now the thing is you can't be sure which companies you'll actually want to buy from in the future. Apple is a great example - most people who own iPhones today would never have thought that a niche computer maker would produce their most important and personal devices.

This is why so many financial experts are proponents of indexing. When you buy an index, e.g. VTI which is Vanguard's Total US Stock Market, you're buying a slice of, essentially, every company in that stock market.

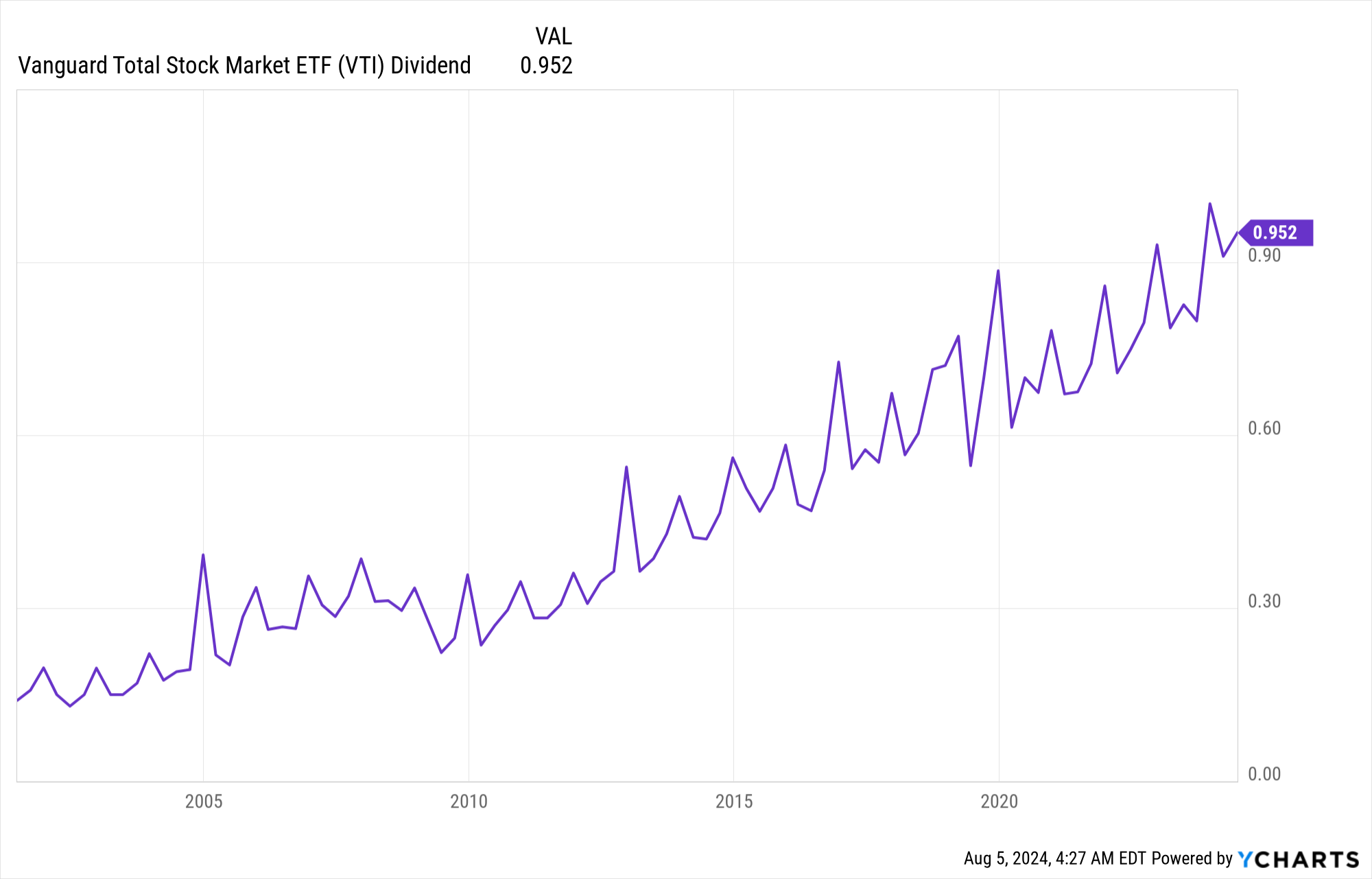

You can see here that over the last 20 years, similar to Reality Income, the VTI dividends has climbed pretty reliably (most of the choppiness is due to seasonality).

The VTI index fund is market cap weighted - this means that the bigger a company is the more of it VTI will own. As various market participants bet on various companies their value goes up and down and this ends up reflected in that market cap weighting.

There are two ingenious things about this:

1) It's very tax efficient. Since the fund buys stocks and then allows them to float up and down with the market movements you're not having to constantly buy and sell (thus incurring transaction costs and tax liability on the gains).

2) You're benefiting from all the research and investment work of the smartest people on Wall Street. As they move the price around your personal allocation moves in lock step. Basically it's a vote from the smartest investors in the world as to how much society in general will want to consume from these companies in the future - and how much profit they'll derive from that activity.

By buying an index fund you're allowing the market of investors to vote for you on who they think the most profitable companies of the future will be. Your long run purchasing power will be invested into the real companies producing the real things you want to buy in the economy.

You just have to make sure you can weather the short term storms where valuations change rapidly.

What to do

1) Figure out how much short term reserves you need and place that into something safe (see Allocating Capital: Fixed Income)

2) Place the rest in a diversified index fund

3) Get on with your life

This, in essence, is the argument of Nick Maggiulli's book Just Keep Buying - which is a good tagline when you think about how you would want to approach your personal ownership of the global economy.