Allocating Capital: Fixed Income

“No, the thing to buy was Liberty Bonds, and we bought four of them. It was a very exciting business. I descended to a shining and impressive room downstairs, and under the chaperonage of a guard deposited my $4000 in Liberty Bonds, together with “my” bond, in a little tin box to which I alone had the key.

I left the bank, feeling decidedly solid. I had at last accumulated a capital. I hadn’t exactly accumulated it, but there it was anyhow, and if I had died next day it would have yielded my wife $212 a year for life—or for just as long as she cared to live on that amount.”

- F. Scott Fitzgerald, “How to live on $36,000 a year” April 5, 1924

“Safe” vs “Risk” assets

Every investor faces two major risks: losses and inflation. Figuring out how much to allocate to “safe” assets (cash, bonds) and “risk” assets (stocks, private equity, real estate, etc) is a balancing act between these two risks.

The problem and irony here is that “safe” assets are nearly guaranteed to get eaten by inflation, and a reasonably diversified basket of “risk” assets are very likely to perform exceptionally well over a long enough period.

Long enough period is the most important part of this statement.

Over a long enough period inflation will deteriorate the value of cash - if you earned no interest and just let $10,000 sit in an account earning nothing from 1927 - 2023 your $10,000 would lose ~95% of its purchasing power.

$10,000 losing 10% of its value by the end of WW2, 90% by the time Paul Volcker retired in 1987

Of course the nominal value of your cash doesn't actually decrease - everything else just becomes more expensive.

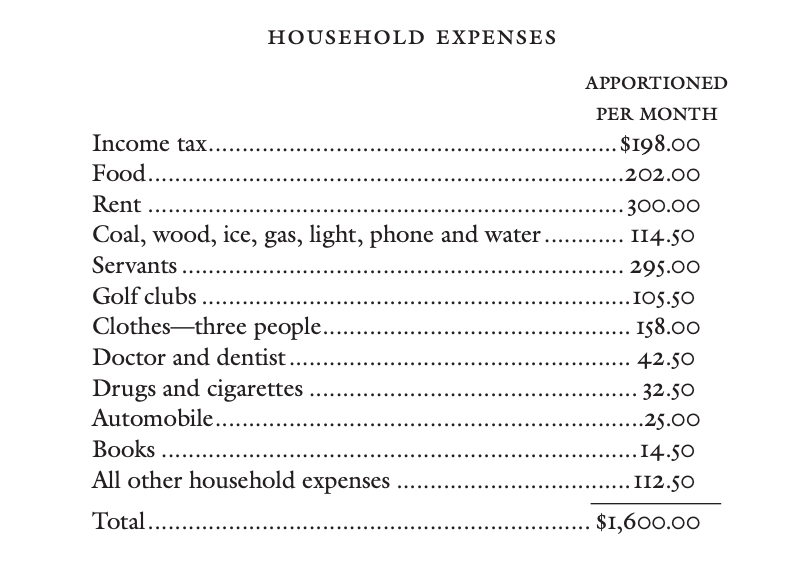

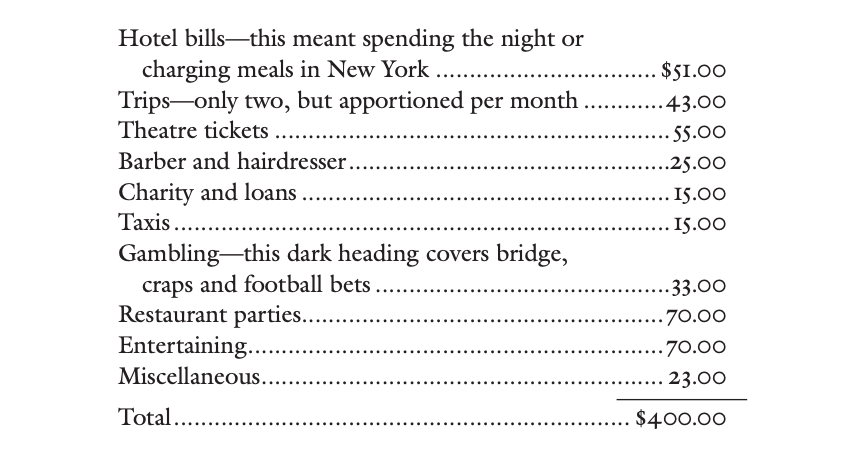

F Scott Fitzgerald wrote “How to live on $36,000 a year” in April 5, 1924 as a bit of a self critical joke - at the time it was a vast sum to spend. In the essay [0] he and his wife tally their expenses finding they spend about $24,000 a year on household and pleasure expenses - and yet are somehow missing another $12,000 per year they can not account for.

Let's assume we wanted to construct a portfolio that would allow Francis and Zelda Fitzgerald to maintain their spending from 1927 [1] until 2023.

Adjusted for inflation, $36k in spending would need to become $240k by 1987

Perhaps we could just put them in a pure stock portfolio? It's well known that stocks outperform bonds and cash over the long run. Let's assume they have the incredible sum of $900k in 1927 - which is 25x their annual spending of $36k.

On the surface this seems very easy - just stick that $900k in a broad stock market, spend what you need and let the rest compound. The returns to doing that would be amazing over the long run.

$900k in 1927 would turn into over $7b if left to compound for the nearly 100 years

The problem here is that they're living off their portfolio so we have to account for spending. If we take the same $900k and spend out of a S&P 500 portfolio - adjusting up our spending for inflation over time you'll see that we run out of money. This is both because we have a few bad years at the beginning and our spending marches steadily upward due to inflation.

$900k gets crushed by spending and stock market failures

This problem is so well known in the investing and wealth management space that it has a name: Sequence of Returns Risk. When you start spending out of a portfolio you need to be careful you don't eat the seed corn during the bad times when valuations drop.

You see in the chart above that even though you didn't spend all of your money during the crash of the late 1920s and early 1930s - you spent and lost enough to not make it out alive over the long run as an investor.

What if you just invested in "safe" assets? In this case 3mo Treasury Bills (T-Bills), basically the safest asset we can buy.

$900k, adjusted for inflation, gets spent quickly if you're not making good returns

Well you run out out money a bit later than in the pure "risk" portfolio - but not by much. Still a failure.

If we split our portfolio 50/50 between stocks and 3mo T-bills we'll make it to 2023 even as we keep pace with inflation spending lavishly all through the depression, WW2, the stagflation of the 70s, the dot-com bubble, the 2008 crisis, Covid, etc – and we'll come out on the other side with over $240m!

50% stocks/bonds holds up

This is because our $450k buffer, 12.5 years of runway, is enough to overcome that Sequence of Returns Risk.

In our simple model here we fully draw down that "safe" asset sleeve before digging into any of our "risk" assets - and this gives the risk assets time to compound into a very large sum - large enough that neither our spending nor the gyrations of the market put us in mortal peril.

The late great Charlie Munger highlighted how important it is not to interrupt compounding unnecessarily: By having a large enough "safe" buffer to spend down you can avoid interrupting compounding.

This is an extremely simple model, assumes no rebalancing, adjustments to spending outside of inflation, or other important factors any real investor would consider.

The point, however, is to show that constructing the appropriate "safe" and "risk" allocations allow you to ride out a rough start (i.e. using your portfolio starting near the peak of the 1920s bubble) and ultimately thrive.

The right allocation is generally some split - not all safe and not all risk.

Safety buffer sizing

The buffer is not about a portfolio % and more about how much money you need to pull out in the near term. It's about your time horizon and your cash needs.

Ideally you want the largest possible allocation to risk assets that you can have without risking blowing up and going negative. How much you are able and willing to adjust your spending, how much your spending is relative to your asset base, how risky your income is - these will all impact your risk appetite and "safe asset time horizon" - so there is no one right answer.

A lot of financial debates are just people with different time horizons talking over each other.

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) April 18, 2022

Personally, I like to have a plan that accounts for, say, 10-20 years of bad returns in the stock market. This doesn't necessarily mean I need 20 years of cash.

For me this is some mix of expected income (dividends, interest) plus the principle of safe assets (cash, bonds). For others this could also include earned income, pensions, royalties, etc.

You just need enough buffer and time to ride out any problems and let the compounding do its work.

Other risks in safety

We already talked about, and showed, how inflation can eat a safe portfolio. The other risk with "safe" assets, related to inflation, is interest rate changes.

A fixed income instrument like a bond is a loan you're making - often to a government or company. That loan has a duration - a period within which the borrower will pay it back.

In the case of US Treasuries - you're the lender and the borrower is the US Government. You can buy treasuries that mature in very short periods of time, like a month, or long periods of time, like 30 years.

Most of the time you get paid more to lend for 30 years than you do to lend for 3 months. At the time of writing - this is not the case, though - right now we have an inverted yield curve where the short term bonds pay more than the long term bonds.

Below I've created a short video that you can watch (or simply scrub around on to see the curve move) of the US Treasury interest rates by duration for the last 33 years.

I think there are a couple important take-aways from this video:

1) The curve is actually flat-ish more of the time than I thought - therefore you might not be getting paid that much to take on the extra duration/interest rate risk most of the time. William Bernstein makes a similar point in The Intelligent Asset Allocator - generally advocating for holding shorter term bonds.

2) The short end of the curve moves around a lot - and the long end of the curve has been declining for a long time and is still low by historical standards. This means that the risk/reward on long bonds isn't great - since you'll lose money when long interest rates go up - and there's less room for gains when long bonds go down.

There are, of course, smart counterpoints to these arguments (if there weren't then there wouldn't be enough buyers for those long bonds to keep their yields low!) – The most important counterpoints I can think of are:

- The US Government has enough debt that they can't keep interest rates elevated for a long period of time.

- If you buy a ladder of bonds that 'maturity matched' to your obligations (i.e. maturing around the time you'll need the money) you'll nullify most of your risks

I think these points are reasonable - but the latter point is the most compelling for me. However - this brings us back to the question of time horizon. I think the "safe" asset allocation sweet spot is really in a 10-15 year horizon - outside the scope of a real "long bond" which is a 20-30 year instrument.

For me, personally, I'll keep my duration in the short and possibly intermediate sections of the yield curve. If the curve un-inverts, especially steeply - I could get more excited about the intermediate or maybe even longer end.

Taxes

If you pay US taxes you may want to consider municipal bonds. Municipal bond income is free of tax at the US Federal level - and depending on the state/municipality of origin may have a preferred status in your state as well.

The historical default rates are very low (though, municipalities can't print their way out of trouble like the US Federal Government, and munis do sometimes face losses).

A simple comparison to make is to see what your "tax adjusted" yield would be on a US Treasury.

Adjusted Yield = Nominal Yield / (1 - Marginal Tax Rate)

You can then compare that tax adjusted yield to what you might get on a tax-free muni bond.

Less safe bonds

There is, of course, a whole exciting world of less-safe bonds. High yield bonds can be a great way to strike a balance of less-risk-than-stocks but more-return-than-safe-bonds. More on this another time.

Focus on safety in the short run; opportunity in the long run

The most important thing about "safe" asset allocations is sizing them appropriately. Sizing is about time horizons.

Too little safety in proportion to your spending or capital deployment needs will cause you to hit a crunch at the worst possible time when markets seize up. This is a short term buffer.

Too much safety will cause you to be eaten by inflation over the years and miss out on the compounding growth of ownership asset classes. This is the long term risk.

Size your fixed income allocations to give yourself an appropriate buffer for your needs. For you that might be 5 years or 15 years. As with all asset allocation choices I think it's a rather personal decision.

For the Fitzgeralds all of this investing advice would have been rather unnecessary as they preferred to spend more than they made, negating to need for these dull long term investing strategies.

Further Reading

- Specifically on US fixed income: The Bond Book, Third Edition: Everything Investors Need to Know About Treasuries, Municipals, GNMAs, Corporates, Zeros, Bond Funds, Money Market Funds, and More

- Asset allocations: The Intelligent Asset Allocator: How to Build Your Portfolio to Maximize Returns and Minimize Risk

- Interest rate history: The Price of Time

- Federal Reserve Policy & Interest Rates: The End of Alchemy, Keeping at it

[0] https://loa-shared.s3.amazonaws.com/static/pdf/Fitzgerald-36000-a-Year.pdf

[1] The year Aswath Damodaran's data set on returns and inflation begins https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html

Thank you to the Manim team for the excellent animation library.