AI Labor Part 2: Rollout

"The future is already here — it's just not very evenly distributed" - William Gibson

In AI Labor Part 1: Leverage we covered

- Defining leverage - Why being trustworthy and likeable will be even more rewarded in an AI future

- Copilots vs Autopilots - Why most near term economic impact will come from augmenting human workers

- Leverage Metrics - How to think about lots of workers becoming 2-3x as productive and valuable

Investors will want to see rollout of these technologies because they'll make firms more profitable. Top performing employees will see opportunity to earn more by scaling themselves.

Now we'll talk more about the process of applying AI to various jobs - and some mental models for thinking about which jobs/industries will be impacted sooner vs later.

As this change rolls out across the economy it will happen unevenly according to various AI Labor Impact Factors which will inform the extent and speed of change.

AI Labor Impact Factors:

- Model capabilities: The power, efficiency, and versatility of models being produced

- System integrations: Our ability to integrate these models into real world workflows including data on/off ramps

- Capital requirements: The cost of producing, running, and integrating models into workflows

- Social norms: What customers will accept in terms of norms for dealing with AI systems

- Regulatory regimes: What governments will allow AI systems to do

For each opportunity to deploy AI in a way that enhances or eliminates labor you can think about the opportunity and challenges through these five lenses. Here are a few very brief examples:

Customer Service - We're already seeing some quick disruptions here (e.g. Klarna).

Models have the capabilities to do first line support interactions, the system integrations are suitable for today's simple chat interfaces.

The capital requirements here are minimal since a business can ride on top of investment already made by OpenAI/Microsoft.

Socially this is an easier change to make since the bar for a lot of customer service is already low.

This isn't a protected space for regulatory reasons - and as Klarna points out in the article above the workers impacted are subcontractors. This makes the HR process easier.

Lawyers - Given that a lot of legal work is just text processing this domain scores well for model capabilities, system integrations, and capital requirements.

This gets more challenging when you think about social norms - customers might not be excited to pay high fees for AI generated legal advice - and the stakes for getting things wrong here are high. Further - many legal firms bill hourly and so the adoption of technology that reduces hours isn't obviously accretive to their bottom line - billing norms will have to change.

Further, the legal profession - as the creators of our entire regulatory environment, are quiet adept at insulating themselves. While AI will doubtless impact this profession it's not going to be as swift or aggressive as something like customer service.

Taxis - We now have models and integrations that can drive cars – Waymo announced a launch across four cities earlier this year.

The capital requirements are high, though, with many billions of dollars spent by Waymo alone on R&D. Further, each Waymo car is estimated to cost in the neighborhood of $200k.

People seem to like taking automated taxis and regulators are coming around to allowing them.

The regulatory process has been a large investment for these firms - and will likely require jurisdiction by jurisdiction approvals.

Self-driving is such a large and iconic market, though, that all these investments have been underway for 15+ years and we're now seeing the results.

Plumbing - The trades, using plumbing as an example, seem like an area ripe for disruption with a dwindling population of workers and associated rising prices.

However, we don't today have good models (or likely even training data) for these sorts of tasks. The integrations of these models into the real world will require massive innovation in robotics that will come with both high R&D costs for the models and huge capital outlays to build each incremental robot.

AI impacting this domain in any way at all is likely a 2030+ phenomena.

For most language heavy knowledge tasks we can will likely see substantial impact in the next 5 years - even without much incremental base model improvement (where there’s plenty of evidence we’ll get more gains).

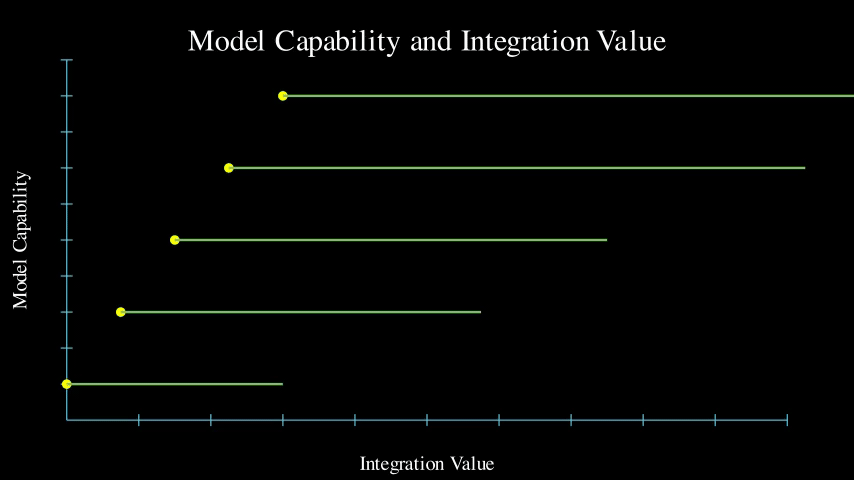

Models and Integrations

Model capabilities are clearly charging ahead in a shocking and exciting way.

System integrations are still getting figured out.

The way I think about it is that as models get better it becomes faster and easier to integrate them into workflows - but there's still a lot of work to do to make the models actually deliver integrated value.

Over time we can harvest additional integration value from the same model - but better models yield more value faster

Integration value is delivered by producing real business outcomes in the form of incremental net margin.

The integration work today is multi-fold:

a) Models need to be harnessed such that relevant data can be fed into them with useful outputs returned. Think of this as Model IO.

b) Models may need to be trained, fine tuned, prompted, scaffolded, etc to produce sufficiently useful outputs - experimentation is often required here to get good enough results. Even knowing what "good enough" is can be a process of working with customers and users.

c) Workflows need to be modified to integrate this new tooling, and staff need to learn how to use it

There's a lot of work to do - and it will take time to do that work, especially where there are stakeholders to convince, risks to manage, and teams to train. We'll need to figure out the AI Experience (AIX?) - kind of like the UX - for both the AI models and the humans.

So, as the graphic above shows there are actually multiple threads running at once eating up workloads and transitioning them from the pre-AI world to the post-AI world.

There are years of gains to be harvested from existing models.

When thinking about the impact on labor costs and business profitability it's essential to realize that massive returns here do not require further model enhancements (even though we will undoubtedly get them). Existing models today are sufficiently powerful to create large economic upsides (and correlated labor market dislocations).

Further, as models become more powerful we should expect that integration times come down and new workflows will be amenable to AI.

Today developers need to pre-process data more, and/or provide more scaffolding to get sufficiently good results.

For example - today if you want an AI system to read information out of a contract and summarize some conclusions for you about that contract you'll want to structure this as a multi-stage process where you do some extraction work using one bit of code asks the LLM to return structured information about the contract and then another bit of code uses that structured information to outline to draw conclusions.

Future models or compound AI systems may be able to (reliably) do more of this multi-step thinking on their own without as much engineering effort put in to deliver this sort of thinking "scaffolding." This is explored more in Situational Awareness by Leopold Aschenbrenner.

I don’t see a future where this integration work is eliminated - but it’s quite easy to see how better models will reduce it. For example: Models will ultimately be able to write integration logic semi-autonomously.

So, we should expect to see ripples moving through the entire labor market - especially the white collar labor market over several years - regardless of what happens to model improvement.

We don't need AGI to see 2x+ labor efficiency in many text heavy workflows - we just need better tooling, process integration, and time for these to play out.

Capital Requirements

One of the earth shaking things about the new LLM AI models we're working with is that they can create substantial business value when used "zero shot" - i.e. without specific training for that use case.

For many use cases we no longer require a large library of labeled data or a lot of feedback cycles with the model to get results good enough to augment human labor.

This means that you can use an off the shelf model and simply pay the cost of running data through that model (inference) and avoid the cost of creating a new model (training). Training is far more expensive than inference so this has very important implications for capital requirements.

There are, of course, half-steps to training like fine tuning. These leverage existing models and are significantly less expensive than training new models.

GPT4 may have cost "Over $100m" to train but it can be amortised over many customer use cases (OpenAI is reportedly at $3.4b revenue run rate).

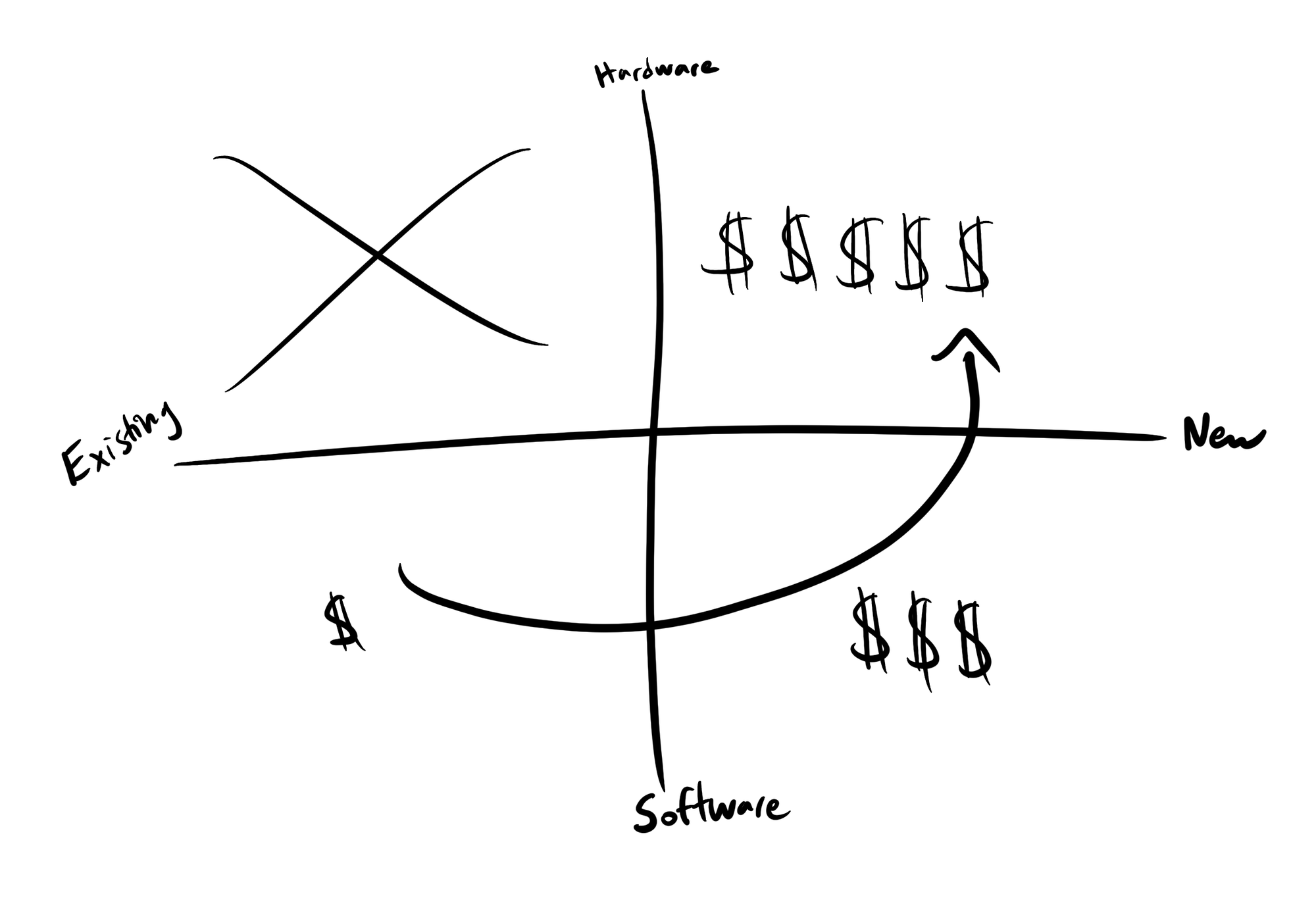

So for a lot of knowledge tasks you can use an "Existing" model instead of a "New" model making capital requirements modest. Here the economics are in favour of a faster productivity increase and a rapid change to the labor market.

In other domains there will be a need for specialized models - NVIDIA has a VP of healthcare, Kimberly Powell, who regularly posts/talks publicly about how large the specialized healthcare model opportunity will be.

These improvements will be incrementally more capital intensive - and likely more restricted to domains where there is a large appetite for capital deployment given the cost of training new base models.

Everything that we've talked about so far has been in the "Software" domain where the fundamental interaction of the AI is ingesting and dispensing information.

There will be hardware-oriented AIs (indeed, Waymo and Tesla with their self driving efforts, or Amazon with warehouse automations are already delivering domain specific versions of this) - and these will require new models (hence the X in the diagram).

As children growing up over the last 100 years we've been promised robots - but these will require not just physical bodies - but also new models. The capital requirements here will be vast to produce both - thus delaying the speed at which we'll see labor market impact on both workers and margins.

This is why we've seen some large fundraising in the "AI for physical world" space with new companies led by well known tech industry folks like Fei-Fei Li and Lachy Groom.

For some types of labor in some markets the wage rate is low enough that the cost of building and deploying AI tooling will be insufficiently compelling. I would expect that lower end white collar jobs in New York, California, or London will be automated long before lower end administrative jobs in Athens, Manila, or Hyderabad.

It’s not surprising that we’re seeing driverless cars get deployed in California earlier than most other markets. Labor regulation and cost of living push wage prices up, it’s the nexus of the many of the technical teams working on these problems, and prices are high enough to support a large capital investment.

I expect most physical robotics applications to greatly lag more pure software data oriented use cases both because we don’t yet have the models and training data — and because the capital requirements for the physical implementations will be far higher even when we have models with these capabilities.

Models, integrations, and capital requirements will dictate what is possible from an economic and engineering perspective. Social norms and regulations will dictate what will be acceptable.

Social Norms

On a recent weekday morning in Bangkok I was drinking coffee with my wife while sitting outside one of my favourite coffee stands in the upscale Thonglor district.

We were watching a small drama play out across the street at a condo involving some of the tenants, deliver person, and staff. This made me think about the future of the labor market. The conversation we had sitting there was the spark of an idea that turned into this post.

I have a hard time seeing high end condos in Asia without human guards and gardeners. Part of this may be due to labor costs (and relative capital requirements) but part of this is also an issue of social norms.

Before I moved to Singapore a friend of mine offered me the unsolicited advice to "Embrace the Asian way of life" to which I asked what she meant. Her reply was "Hire help." Part of this way of life is having people you say hello to every day as you enter and leave.

This is true broadly - I was surprised (and slightly distraught) at how hard it was to find a hardware store in Singapore. There is no Home Depot equivalent in Asia as far as I can tell. Americans really are rugged individualists who like doing things by themselves in comparison

In the US I suspect we'll see more AIs and robots not just because the country is very wealthy - but because it's a more isolated society where people like to live alone in big houses far away from other people.

Still, even where there is a strong economic incentive to automate as much as possible I think we'll see social norms around risk and uncertainty dictate a human in the loop for pretty much any high stakes decision.

My first experience deploying AI in a business context was in 2008 when I started building ML algorithms to organise pools of medical bills and flag candidates to review more deeply where there was likely fraud or overly aggressive billing.

We used large datasets where doctors, nurses, and professional bill reviewers had tagged bills in a classic ML workflow where you use an algorithm (in our case a Support Vector Machine / SVM) to figure out the structure from all that data the human workers already organized for you.

The promise of this work was to improve the amount of fraud the firm could detect - and because the firm got paid by reducing bill cost the goal was fundamentally to make each of the human reviewers more effective.

Indeed as we started to use the system early on there were two interesting effects that stuck with me:

a) People were quite nervous about the blackbox nature of the algorithm - it was a tool they were willing to leverage but a certain distrust existed because it was both automated and probabilistic.

b) The most promising usage of the tooling was to analyse pools of medical bills that we otherwise wouldn't have had capacity to work on at all and cherry pick the most likely to be worthwhile candidates for closer analysis.

Thus, with this algorithm, despite delivering automation, we probably did more to increase the total amount of work done - even as we increased efficiency.

This is the sort of paradox where you can see a decrease in labor intensity and an increase in labor demand at the same time.

This phenomena mirrors what Mary C. Daly of the SF Fed says here in this clip:

Head of the San Francisco Fed Mary C. Daly says AI is augmenting rather than replacing workforces because "no technology in the history of all technologies has ever reduced employment" pic.twitter.com/z7PyGaZmSM

— Tsarathustra (@tsarnick) July 18, 2024

Speaking of governments - even if we could auto-pilot everything, I don't think we'll be allowed to.

Regulation

Regulation will limit the amount of auto-piloting for two reasons:

1) It's difficult to hold machines accountable for decisions - and creators of machines will do whatever they can to indemnify themselves

2) There will be a desire to promote employment and share prosperity

There are already laws restricting who can own law firms (lawyers!) and requiring that there is a signer who takes responsibility for various corporate or tax filings.

Ultimately it's impossible to have a machine or algorithm be responsible - and governments will demand a human throat to choke if things go wrong to ensure accountability.

Separately, countries institute regulations to protect workers. They often also look to protect certain classes of workers - e.g. preferring you employ citizens vs foreigners.

It seems quite plausible that if AI begins to reduce labor demand countries will enact even more laws requiring a human to sign off on certain decisions.

Conclusions

I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is to-day. - John Maynard Keynes, 1930

Near term impact of AI is much easier to reason about. In the longer run (5+ years) we may need to deal with some wild superintelligence scenarios (see more in Situational Awareness). Shorter term impact on the labor market will be clearer.

Near term effects (next 5 years)

- AI will make the most trustworthy and valuable workers able to do more work in the same or less hours improving both quality of life and compensation.

- More highly leveraged workers will be able to do more productive work – and more damage – making it wise to align their incentives more like business partners

- Businesses will share some of the increased efficiency with workers - but a lot of it will flow back into the business as higher margins benefitting owners (including employee owners, pension funds, etc)

- White collar employees that can't be trusted to make good judgements will be increasingly irrelevant and will face greater unemployability issues - AI systems will be far superior to people with intelligence or integrity issues.

- All of this will happen slowly and then quite rapidly in domains where information processing is the main workflow

- We're not getting rid of humans entirely in most workflows, though, humans will be desired for their relationship capabilities, judgement, accountability, and to fulfil legal requirements for a person.

- Integration of AI models into workflows will accelerate as AI tools help us build better AI integrations more rapidly.

Longer term & Second order effects

Even if we see some pretty dramatic levels of automation and leverage for a wide array of workers I can't foresee a world where work really "ends" - though it could change dramatically in my lifetime.

I agree with Steve Cohen that workers may work fewer hours and engage in more leisure due to advances in technology and AI. He thinks investing more in things that people will do with more leisure time is a good bet because of this.

There is a long history of people predicting this sort of thing – and being at least somewhat wrong.

In 1930 John Maynard Keynes famously wrote an essay on the "Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren" in which he discussed a future of prosperity and an end to the full work week.

The course of affairs will simply be that there will be ever larger and larger classes and groups of people from whom problems of economic necessity have been practically removed.

He goes on to suggest that due to "Technological Unemployment" we may all end up working 3 hours a day (15 hours a week) to satisfy our inner desire for productivity.

Joe Lonsdale points out that this "needs satisfying" paradigm isn't quite right:

We intrinsically crave heightened sensual experience, superior physical health, a richer understanding of our world, and elevated artistic achievement — as well as more extensive peace, prosperity and justice for our fellow man. It is in our nature to continue to climb.

No matter how much automation we deliver - we will always come up with ever more extravagant things to design, create, and want.

If we really do get massive automation though there will be more and more jobs that look like "minding the virtual shop" where a human needs to be in the loop, reviewing things, on call - but this will be done with ever more flexible schedules and locations. This will bode well for Cohen's golf bets.

Despite the mini-boom of software engineers being asked to "RTO" (return to office) the broad trend in tech is towards more flexible working conditions and I expect that to extend - and expand to other job functions.

One of the complex things about talking about the future is that there isn't just one future. Technology and greater societal wealth will allow each person to live a life that suits them. The choices will not be evenly distributed.

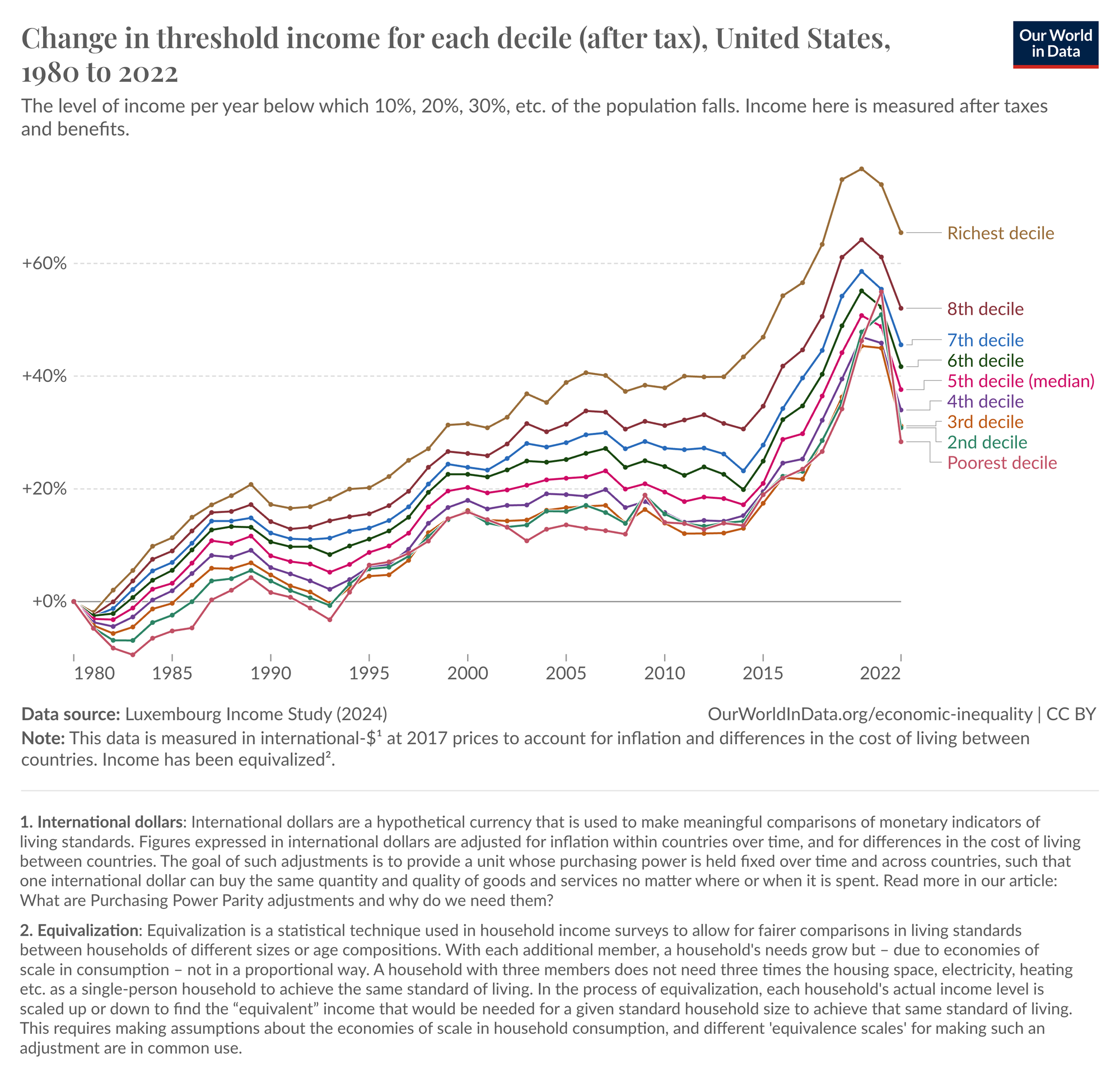

Since 1980 every decile of the American worker by income is better off - but the upper deciles are more better off. This makes sense when you think about the compounding effects of leverage - and I think it will likely continue to happen.

More and more people are able to work flexibly, remotely, part time. Even when people are at work they're listening to music or podcasts on their earbuds, texting on their phones, or stopping to read articles or share memes.

For the most driven and focused workers out there AI will let them imagine vast new possibilities and give them almost infinite leverage. For those who want to work to live rather than live to work I bet there will be more opportunities for shorter, more flexible, less taxing work weeks.